History of India and Pakistan is intertwined and contributions of Pakistani scholars and politicians to the fundamental aspects of Indian democracy are example of shared history that deserves to be recognised

As India is in the thick of a mammoth electoral process to elect 543 Lok Sabha members, few recognize the subtle contributions of Pakistan to this democratic exercise.

A notable yet overlooked connection is the indelible ink marking the fingers of approximately 970 million voters who are coming to vote in around 12 lakh polling booths spread across the country.

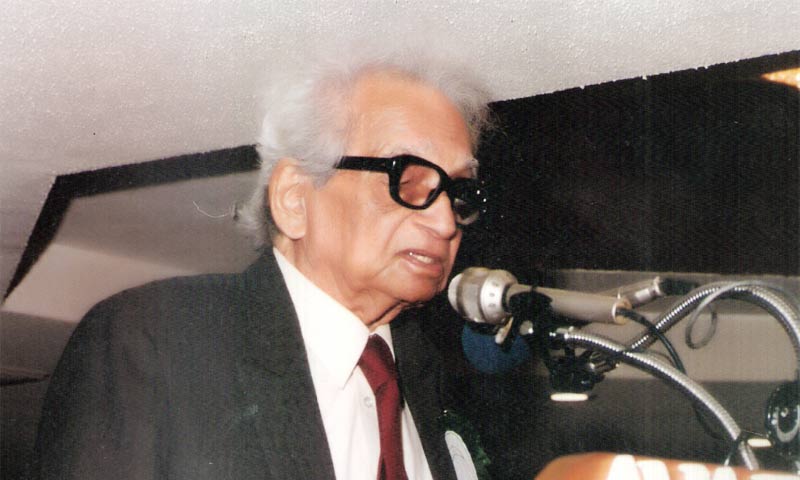

Not many people know that this ink is a legacy of Pakistani scientist Salim-u Zaman Siddiqui.

This practice of voter marking, integral since India’s first general elections in 1951, is crucial for preventing vote tampering and ensuring election integrity.

Interestingly, the ink’s origins trace back to Siddiqui, the founding chairman of the National Science Council of Pakistan founding chairman and younger brother of Khaliq u Zaman Siddiqui, a prominent leader of the Muslim League.

Initially working under Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar at the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research pre-partition, Siddiqui developed this ink in response to a British directive during the 1946 Constituent Assembly elections, aiming for a solution that was effective yet skin-safe.

After many experiments, Siddiqui mixed silver chloride with silver bromide and developed an indelible ink that stuck to the finger. The ink, which proved to be permanent and harmless, represented a significant advance in voting methods.

Although Siddiqui went to Pakistan after the partition of the country, his innovation remained in India and became an integral part of the Indian electoral system, which is now used in over 30 democracies worldwide.

Gopal Krishna Gandhi, a former governor and grandson of Mahatma Gandhi, even suggested naming the system “SiddikInk” to honour its creator — a suggestion that has yet to be officially recognised in India’s current political climate.

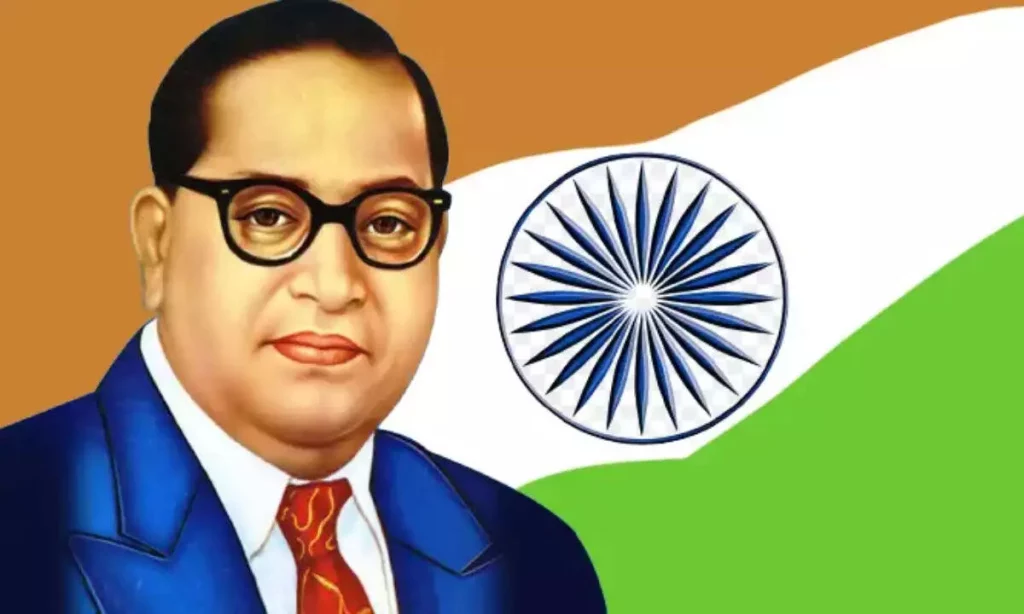

Another significant, yet understated, Pakistani contribution to Indian democracy involves helping Dalit leader Bhimrao Ambedkar, revered as the architect of the Indian Constitution.

Facing an election defeat in Bombay, largely due to maneuvers by Congress leader Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Ambedkar’s entry into the Constituent Assembly was facilitated by the Muslim League.

Leaders like Pakistan’s first Law Minister Joginder Nath Mandal and Hussain Shaheed Suhrawardy ensured Ambedkar’s candidature for a seat in Jasur-Khulna (now Bangladesh), solidifying his role as chairman of the drafting committee.

Six months later, when Jasur-Khulna went to East Pakistan as part of the Redcliff Award, India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru asked Congress member M. R. Jayakar from North Mumbai to resign, paving the way for Ambedkar’s return to the Constituent Assembly to continue as the Chairman of the Drafting Committee.

Moreover, Ambedkar’s post-Constitution political journey was not smooth. Despite his monumental contributions, he suffered electoral defeats and was often side-lined by both the Congress and other political groups, reflecting the difficult dynamics of caste and politics in India.

But how ironic it is that soon after the Constitution was introduced, in 1951, when the first general elections were held in India, this creator of the Constitution again suffered a major defeat in Bombay. In 1954, he tried his luck again in the by-elections in Bandra (Bombay), but again he was defeated.

Interestingly while Ambedkar became the first law minister of India, his political guru, Joginder Nath Mandal was appointed law minister and chairman of the drafting committee of constitution in Pakistan under Jinnah. He was a strong advocate of Dalit-Muslim unity.

His dreams soon soured after Jinnah’s death. Soon clashes started between him and Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan and his cabinet colleagues.

The massacre of Dalits in East Pakistan, now Bangladesh, in 1950 shook Mandal so much that he fled to Calcutta overnight and handed in his resignation to the Pakistani Prime Minister.

After his return to India, Mandal was always viewed with suspicion and was never able to regain his pre-independence status. He spent all his time looking after refugees (mostly Dalits) from East Pakistan. No political party was willing to accept him. He finally died in Calcutta in 1968.

The history of India and Pakistan is intertwined in a way that goes beyond conflict and partition. The contributions of Pakistani scholars and politicians to the fundamental aspects of Indian democracy are an example of a shared history that deserves to be recognised.

These stories not only enrich our understanding of the past but also teach us something about the complexity of political and scientific cooperation across borders.